wal3: A Write-Ahead Log for Chroma, Built on Object Storage#

Authored by Robert Escriva Sicheng Pan TJ Krusinski Sanket Kedia Hammad Bashir

Authored by Robert Escriva Sicheng Pan TJ Krusinski Sanket Kedia Hammad Bashir

Building a database is a battle against failures. Every bit wants to flip, every pointer wants to dangle, and every invariant seeks to be violated. In the hostile environment of the data center, anything that can go wrong will eventually go wrong.

And when that happens, how will you know? You could react after the fact, building a patchwork of observability to capture the problems seen in production.

This reactive mode of working represents the bare minimum level of care we should expect from our software vendors.

As software engineers, we don't just write code—we construct parallel realities. One reality is the system as it operates; bytes flow from the disk through to the end user in milliseconds. The other reality is our fiction of that system—the things we can see about it and the external effects of the system. This fiction presents things at human scale—on the order of seconds and minutes.

At Chroma, we built a write-ahead log that could exist in both realities simultaneously—one that not only stored data durably on object storage but also maintained an ongoing proof it was doing so correctly.

This is the philosophical and technical story of wal3: how we leveraged a 30-year-old lock-free algorithm, Amazon S3's newest conditional writes feature, and a novel checksumming technique called setsum to build a production-ready log. More importantly, it's a story about building systems twice—once for functionality and once for verification—and why this philosophy enabled us to ship with confidence what conventional wisdom says not to build.

For Chroma, the foundational bet of the storage layer is to leverage object storage to provide data durability, operational simplicity, and system scalability. This design choice enables critical features of Chroma that provide significant value to our customers.

As part of fulfilling this bet, we found ourselves in need of a write-ahead log to serve as the durable core of our system. Chroma's architecture splits the read and write halves of the system, connecting them via a durable log. The write half of the system writes to the log, after which an asynchronous indexing service builds indices from the log for the read half. The read half of the system consults the latest index before applying the latest updates from the log to provide an up-to-date query result. While most of the read and write paths are disjoint, the log is common to both. For that reason, it was critical that we selected a design that would enable concurrent readers and writers.

Existing solutions in this space include Kafka (a distributed event streaming platform), WarpStream (a cloud-native Kafka alternative), and Change Data Capture (a database replication technology). This post outlines why these solutions were insufficient for our needs, what we've done instead, and how we were able to go from prototype to production in four months with wal3, a write-ahead logging solution built purely on object storage.

To understand why we built wal3 instead of adapting existing solutions, we examine the requirements and considerations that Chroma's architecture places on its write-ahead log. These requirements include technical necessities, operational considerations, and strategic alignments to our foundational bet.

Our write-ahead log must satisfy these core requirements to be compatible with Chroma's foundational bet on object storage:

These four core requirements guided our search, but there were several additional considerations that played into our decision to build our own write-ahead log. Unlike the core requirements, these considerations were negotiable for the right engineering trade-offs. These concerns included:

The combination of these additional considerations and core requirements guided our decision to not adopt an existing log, but instead build our own solution that met all of these requirements. The core requirements were non-negotiable, and building to meet our own needs empowered us to ship a better database.

Our evaluation criteria and process can be expressed succinctly. We looked at systems that were both open source and purely based on object storage and found nothing. We considered building on other systems in a way that compromised this vision, but elected not to because it would be contrary to Chroma's foundational bet on object storage.

After evaluating existing solutions in the ecosystem against our core requirements and additional considerations, we found that none satisfied our unique combination of requirements. The most promising candidates each had disqualifying limitations.

Kafka: Open source Kafka provides durability through local disks. To overcome the failure modes that come from this choice, it ensures availability through replication. This provides a degree of durability, but requires that operators care for the fleet of disks in order to maintain a Kafka cluster. Maintaining persistent volumes and a cluster of disks would greatly undermine the operational simplicity gains that stem from using object storage. Achieving several nines of durability was not feasible within our timeline.

Within Kafka, the unit of scalability is a topic. Topics are largely bound to their clusters in that migrating data from one Kafka cluster to another is possible with operational hand-holding, but not in the general case. In practice, most people building with Kafka have a non-trivial shim layer on top. This shim is typically responsible for migrations between topics, managing the topics, and general scalability concerns. This routing layer is complex, involving information about Kafka's deployment topology, the mapping from collections to topics, and, eventually, the mechanism to move Chroma collections between clusters.

WarpStream: WarpStream is a disk-less, Kafka-compatible implementation of event streaming built on object storage. We consider WarpStream to be most directly comparable to wal3 because both are log-like services built on object storage. WarpStream represents great engineering, but it isn't open source. For that reason alone, we could not consider it.

The WarpStream team implemented a faithful recreation of Kafka. wal3, in comparison, doesn't support most features of Kafka. It supports read, append, and trim from a log under a prefix on object storage. This simplicity works in our favor, implementation-wise, but does mean that if you're reading this post to evaluate wal3 in comparison to WarpStream you should carefully evaluate whether these are limitations that affect your use case.

Change Data Capture: Change Data Capture on top of most any SQL database would enable us to write data and then roll up the history of writes using a process that applies the writes in order. A SQL database like PostgreSQL serves as an ideal foundation for this approach. To make such a database scale, we would need to have an independent stream per collection; otherwise the resulting system would not be scalable. There is no CDC system for any of the primitives Chroma builds upon, so we would have to build CDC from scratch.

Additionally, none of these systems support the scalability requirements of Chroma. Each Chroma collection requires its own independent stream of updates, and these systems would require us to manually shard collections across multiple instances rather than providing per-collection scalability. To enable Chroma to scale on top of one of these systems, we would need to deploy multiple instances and manage the distribution of collections across them. This would necessitate additional code paths and architectural components for managing distribution across the multiple instances. This architecture would require a routing layer, failover mechanisms, and migration strategies.

Managing a fleet of databases adds significant operational complexity: coordination overhead, correlated failures, and consensus protocol management. When recent advances have made an object-storage-native approach possible because of stronger consistency guarantees, it doesn't take on the burden of managing distributed database infrastructure when there is an enticing alternative.

At the same time we were evaluating ways to improve our log, Amazon made a substantial change to their S3 offering that is the most substantial change since the move from eventual to strong consistency: A new conditional writes feature. This feature allows writers to explicitly say, "Do not overwrite this file," or, "Overwrite this file if and only if it exactly matches a specific, previous digest." Introduced in November, 2024, this new feature enables applications to coordinate directly on object storage without an additional mechanism because the normal upload mechanism now supports this. It becomes possible to do read-modify-write operations by reading the file and writing if and only if no concurrent writes occur. To put it another way, this new feature from Amazon makes it possible to build atomic, lock-free data structures on top of object storage. It made it possible for us to build our log.

This isn't a stretch: The same algorithms that apply to memory can be applied to object storage. When Jeff Bezos specified S3, he wanted malloc for the Internet. If S3 is the malloc of the Internet, then conditional writes can be used to construct and mutate pointer-rich structures. S3 keys are opaque, variable-sized pointers that refer to opaque, variable-sized regions of memory. S3 exposes two methods for atomically manipulating files: "If-match" and "If-none-match". Doing an "if-none-match" allows for atomic allocation and initialization of a region of memory. Performing an "if-match" allows for overwriting contents only when they exactly match—a compare and swap of sorts. In S3, performing an if-match is like atomically deallocating and reallocating a struct; not quite the same as compare-and-swap in-memory, but then again the Internet isn't a single machine. We say that it's different from compare-and-swap because the latter generally doesn't allow substituting variable-sized values while S3 does.

With this new feature and our mental model of S3 as a malloc-like abstraction, we saw an opportunity: Take tricks from the literature for memory and apply them to S3: A lock-free queue built on top of object storage. It's been 30 years since this algorithm was published; this is not a case of, "What's old is new again," but an instance of first-principles thinking that extends across time.

We will start with the in-memory representation and work toward object storage. This algorithm maintains a standard, singly-linked list. This linked list consists of two types of structures: Linked list nodes and a header that serves as the container for the list. The update algorithm is simple: Load the header's pointer to the linked list node, and store it in the new node's next pointer. Then, perform a compare-and-swap the head's pointer to transition it from the existing value that was loaded to the address of the new linked list node, atomically linking the new node into the data structure. This simple algorithm mirrors the standard linked-list prepend algorithm with a crucial addition: It supports concurrent prepends as if the prependers were synchronizing with a lock, except there is no lock.

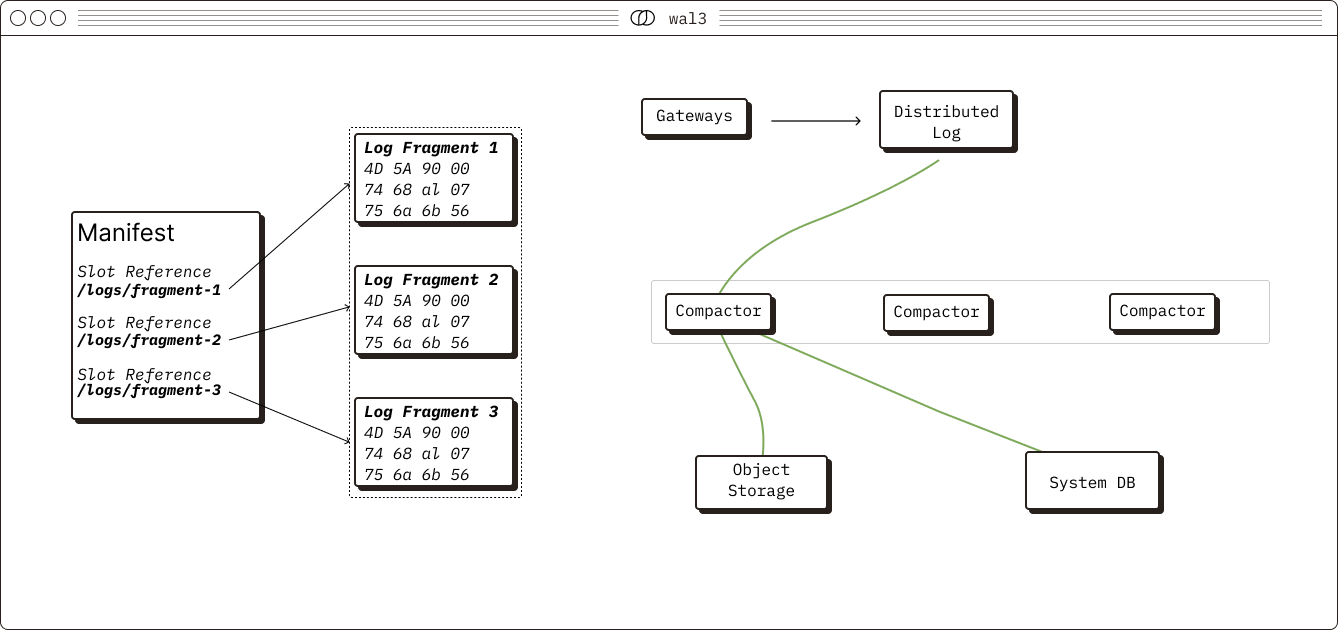

In our object storage-backed world, we only have files. So we will use a file for the linked list node and we will use a file for the header. For clarity, we call the former fragments and the latter the manifest. Where we would allocate a linked list node in memory, we put a file if and only if it doesn't exist. We use if-match on the entire content of the manifest to add the atomically update it to reference the new node. It's the same algorithm in a new context.

Graphically, the isomorphism between the algorithms is readily apparent. In the first step, there are two stationary lists; the memory-bound, pointer-rich list is on the left and our manifestation of it is on the right.

The first step to pushing onto the log is to allocate a new node. In the classic world, this is a memory allocation. On top of S3 this is an "If-none-match" that will make sure Node 3 is created by the log. Note that at this point, neither the head nor manifest know anything about the new node.

In the final step, a conditional operation on the head updates the head to refer to the new node.

We saw an opportunity to improve Chroma and make it scalable in the number of collections, capable of high throughput, and with acceptable latency. The challenge would be making something that works on paper also work in practice while ensuring it was robust and reliable.

Leveraging the algorithm outlined above necessitates writing things ourselves, mostly from scratch. To our knowledge, no one has published an implementation of that algorithm on top of S3 before, and making it work well requires tricks beyond those used with micro-architectural locking primitives. This is where we introduce an additional engineering technique: an order-agnostic checksum called setsum that provides complete coverage of the log. By using a checksum that can provide integrity over the complete log (100% of its data) wal3 provides a tool by which operators can continually verify that it is working as intended.

To understand setsum, let us first develop a shared understanding of a traditional checksum. A traditional checksum is a function that turns a string into a digest: fn checksum(String) -> Digest. It takes an arbitrary string and returns a digest. Any change to the string—even a small one—and the digest changes with high probability. Consider this small change from "hello" to "hallo":

Completely different digests from similar inputs!

The advantage of traditional checksums is that you pair up the data and checksum, maintain them together, and if either goes missing or gets corrupted, it is no longer the case that you have two matching pieces of entangled data. A bit flip in the data or the checksum will, with high probability, manifest as a checksum mismatch and a missing checksum or missing data indicates corruption. A system that demonstrably maintains the data and the checksum together is therefore significantly more robust than a system without checksumming.

We use the term, "traditional checksums", because the fn checksum(String) -> Digest is just one form of a checksum. We could imagine instead that we want to construct a checksum over some richer data structure than a string, e.g., a tree. A Merkle tree exemplifies this approach: each node contains a digest of its children, recursively building up to a root digest that protects the entire tree structure. Such a data structure could be seen as fn checksum(Tree) -> Digest.

Our goal is to create a function fn checksum(Log) -> Digest, which necessitates somehow digesting the log and maintaining the digest after each update. The log interface only exposes append and trim modifiers, but they need to be fast. We can distill the core requirements of our checksum:

That's right: we maintain a cryptographic checksum over the log content that enables us to validate our data at any time we choose. Further, we can run this validation quite cheaply at critical junctions that would otherwise permanently lose data in the face of a bug. When our data is always validated to be consistent, we can infer our code is keeping the data consistent. Continuous validation of data consistency provides strong evidence that our code maintains that consistency. Given a good enough checksum, data loss without a checksum error becomes a problem so complex that it is less likely than losing data against S3's eleven nines of durability.

The challenge that arises, then, is to employ this checksumming strategy so that we can be sure our log is functioning correctly. Effectively, what we want is a fn checksum([String]) -> Digest where the strings are entries in the log. Adding an element to the log updates the digest to a new digest that contains the new element. Garbage collecting an element from the log should be reflected in the digest as well.

To build a checksum that updates in O(1) time during append and trim operations, we leverage monotonicity of the log: Writes always go to the end, garbage is always collected from the beginning. The digest of the garbage-collected prefix plus the live data should match the digest of all the data. The relationship between the three digests looks something like this:

Notice how, logically, the garbage collected prefix and live data together compose the complete set of all data. If our checksum supported this operation, we'd be able to express the invariant at all times.

The problem in our log is one of classification: We have a total domain of data—a list of log entries—subject to garbage collection and we wish to partition the log entries into two groups: Those to keep and those to garbage collect. No data should be dropped inadvertently and no data should be kept unintentionally. And we want to be able to compute the checksum over this classification to defensively encode two versions of the same decision.

To checksum the log, we use a setsum: An associative and commutative checksum that offers standard multi-set operations over strings in constant time. Where a checksum is fn checksum(String) -> Digest, a setsum is fn setsum([String]) -> Digest alongside tools for performing the multi-set operations on the digest itself. Digests preserve the set nature of the input: The function union(digest({A}), digest({B})) is equivalent to digest({A, B}) in its output, but vastly different in its computational complexity. The abstraction supports set addition, set union, set removal, and set difference in constant time over the digests and single element digest construction in the size of the element—just the operations necessary to protect most data structures.

With a standardized setsum implementation (such as the setsum crate), anyone can provide the digest of the data on the log, and the digest of the garbage-collected data. No matter who computes the digests, the sum of their digests must equal the digest of all data (both live and garbage-collected). It becomes possible to run the process multiple times from different binaries—different implementations or just different releases—and confirm that they at least agree with each other. If the implementations are independent, we get reliability wins; the likelihood that different implementations exhibit the same bug is extremely low.

Here's how setsum's order-independent, constant-time operations work in practice, demonstrating that different sequences of operations on the same set yield identical digests:

Notice that the order of elements and the spurious addition and removal of elements don't matter: The setsum captures the digest for the set {A, B} with set semantics.

To ensure no data is lost, two setsums capture the set of all entries currently alive on the log and the set of the garbage collected prefix of the log. A manifest update that accidentally drops data is likely to appear as a setsum mismatch.

Applying setsum requires engineering discipline to develop two parallel implementations of the same code, entwined within each other. Changes to one must be reflected in the other. By maintaining two implementations, one over data and one in the abstract setsum space, we continually cross-check one implementation against the other. One implementation manipulates the actual log data while the other maintains the setsum digest, and they run side-by-side to verify correctness.

The garbage collection process of any system based upon immutable or append-only storage is the most dangerous spot to lose data. By definition, if you only have one place that deletes data, that's the place that's going to lose data. If you centralize all the intentional data loss into one place, that's where the data loss bugs live.

All our exercise with setsum is for naught if it doesn't catch bugs.

And indeed, it caught several bugs, repeatedly in continuous integration and then less repeatedly in our staging environment.

The most illustrative bug we caught was benign, but educational: idempotent garbage collection would fail. Garbage collecting the sequence of fragments A, B from A, B, C should be permitted, even if A, B were previously garbage collected. When the data is no longer referenced, the outcome should be the same as in the original removal. Our setsum construction actually flagged this case as a bug in our code because we weren't cleanly detecting the idempotent removal. The data removed by the garbage collection plus the data that remained in the manifest did not add up to the expected sum total of all data. A bug caught by setsum divergence! The setsum flagged a potentially invalid operation and the fix was to make the code handle idempotent removal.

That's the key: A setsum says nothing about the data and the data says nothing about the setsum in isolation, but together they establish confidence. Maintaining a matching setsum at all times provides a degree of operational confidence to our development process that has allowed us to ship wal3 including the riskiest garbage collection component.

This post just scratches the surface of the design and implementation considerations for wal3. Instead of continuing to describe the solution to one particular problem Chroma faces, we want to paint with broad strokes the flavor of engineering we're excited to pursue at Chroma. For those seeking a detailed system analysis, there is the wal3 README that goes into all the details of the implementation.

In short, we believe that systems design is about contracts between reality and reality as we see it; reality as we see it is just a fiction. We believe systems exist in two forms: their actual reality and our fictional understanding of them. To us, the programmers, the system's reality is a fiction; we cannot see it, we can only observe it through additional SRE observability and monitoring mechanisms. To the system, this observability is a fiction. Whether due to tooling problems or just measurement error, the fiction presented via metrics, logs, and traces resembles the system itself, but is decidedly not the system itself. The best systems recognize that they must be built twice—once for functionality and once for verification—and encode that within their design. The best engineers recognize the wool pulled over their eyes and don't get blinded by the fictions they create.

In wal3, this philosophy applies to the extreme. We have built, effectively, three systems: One for maintaining a log of data, and one for the digest of that data, and observability that demonstrates how these two halves coexist. The three implementations coexist, entwined such that a move in one system matches a move in the other. A dance between data and checksum reflected in the metrics and traces of the system. Two fictions of the system, cheap enough to embed within the system itself so that the system is self-verifying in steady state.

When you're building a database, it's not enough to believe that it's correct. If you're not constantly battling to gain ground on the bits looking to flip and slide and deteriorate out from under you, you're not building a database, but an approximation of a database. In order to ship wal3 in just four months from prototype to serving Chroma's production traffic, we had to undergo rigorous validation. The setsum construction allowed us to confidently deliver a real system with an operable fiction.